Every spring and fall, hundreds of volunteers across 11 western states take part in a remarkable effort to track the health of shorebird populations throughout the Intermountain West. From isolated wetlands and sewage lagoons to great saline lakes, these surveys form the foundation of the Intermountain West Shorebird Survey (IMWSS), an ambitious initiative led by Audubon, Point Blue Conservation Science, and many partner organizations to fill a decades-long data gap in one of the most critical migratory corridors in North America.

Max Malmquist, Audubon’s Saline Lakes Engagement Manager and a lead coordinator of the IMWSS, describes the project as both massive and deeply personal. “We now have well over 200 survey sites and more than 300 participants,” he says. “What makes it incredible is how rooted it is in the community. We could not do this without our network of dedicated volunteers.”

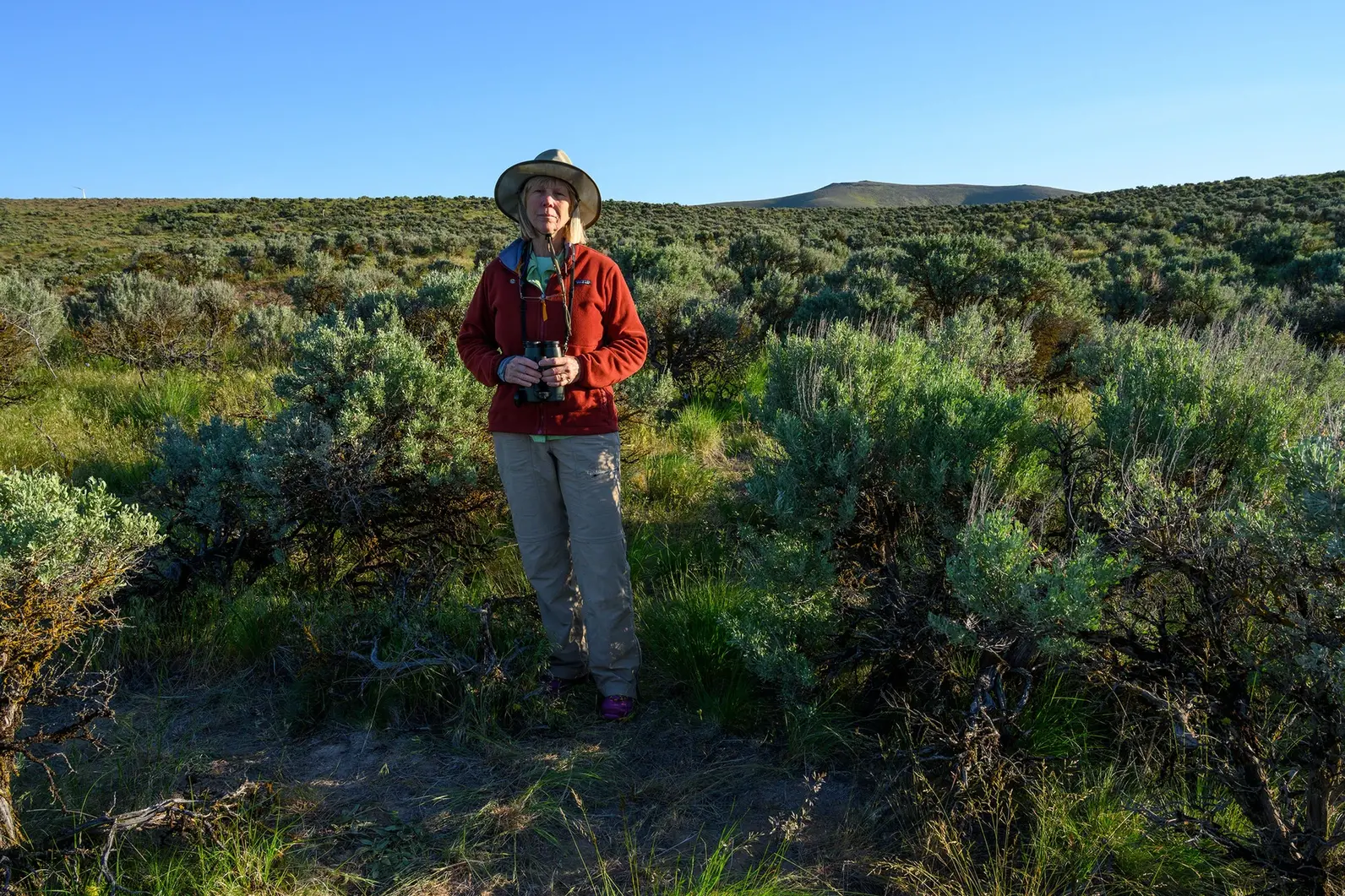

That dedication is evident in the stories of people like Laurie Ness, a member of Lower Columbia Basin Audubon, who manages shorebird surveys in Washington’s Tri-Cities region. Laurie’s involvement began with a call for volunteers and has since grown into a leadership role coordinating site assignments and drawing in data from local birders. “It’s been affirming for me,” Laurie says. “People have stepped up. I’ve built a birding community and connected with really cool folks I wouldn’t have otherwise met.”

Laurie monitors several sites in Eastern Washington each season, often collaborating with other birders to identify important wetland sites for shorebirds. “I just ask if I can use their data,” she explains. “These are excellent birders who know the area, and who help us capture a clearer picture of what’s happening.”

Shorebird surveys in the Intermountain West present unique challenges. Unlike coastal regions, where mudflats provide consistent habitat, interior wetlands are subject to fluctuating water levels—often driven by dam operations or seasonal droughts. Laurie notes that “the key to shorebirds is mud,” and that finding suitable habitat means exploring new and often overlooked sites, such as sewage treatment plants, which can offer consistent conditions when other wetlands dry up.

“It’s not glamorous,” she laughs. “But you’re almost guaranteed to see birds. And I love the thrill of exploring isolated wetlands and discovering new hotspots.”

Another survey volunteer, Spokane Audubon’s Kim Thorburn, echoes this sentiment. “You get to know these places intimately,” she says. “And you come to appreciate the delicate timing and precision required to survey shorebirds during migration. They’re here, and then they’re gone.”

She also emphasizes the broader importance of monitoring shorebird populations. “This project is so meaningful to me because shorebirds are real indicator species. Because they’re long-distance migrators, their presence—or absence—can tell us a lot about the health of the ecosystem and the kind of habitats they need for survival. Their habitats are important for the health of the planet, as well as our own health.”

The spring survey window is especially tight—just one week at the end of April. Volunteers plan carefully, coordinate coverage, and often return to the same sites year after year. The consistency helps ensure the data is reliable, allowing researchers to identify long-term trends in shorebird populations.

That data is crucial. As Max explains, “The last coordinated survey of these wetlands was over 30 years ago. We need updated information to understand what’s happening with shorebirds today and how to protect them.”

The IMWSS partners hope that the data will help inform state wildlife agencies as they revise their State Wildlife Action Plans (SWAPs) and update their list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN). Birds and other animals included on SGCN lists can be prioritized for funding and conservation efforts. Some shorebird species on Washington’s current SGCN list include birds like the Snowy Plover, Red Knot, and Marbled Godwit. Without sufficient data, however, many shorebirds that should be considered for SGCN lists haven’t been included in the past. “This is just one of the many ways in which our program can help shorebird conservation, and garner attention for those species that truly need it,” says Max.

Volunteers like Laurie and Kim are driven by a desire to make a difference. “We’re not managing for shorebirds,” Laurie says. “Their habitats are often overlooked, and many of these isolated wetlands are under threat. I want enough data to make a case—to take action so that we still have these birds in the future.”

For anyone considering getting involved, Laurie offers encouragement: “Volunteer surveys can be intimidating, but we meet people where they’re at. We need everyone—from expert birders to curious beginners.”

The IMWSS stands as a powerful example of grassroots conservation. It is a story not just of birds, but of the people who care enough to count them—people who, with every observation, help build a future where shorebirds continue to thrive.

Interested in joining the Intermountain West Shorebird Surveys? Visit www.imwss.org to learn more and find your region’s coordinator to get involved today.